The magic of schematic learning in Early Childhood

Release Date: June 30, 2023

Last Updated: October 27, 2023

In the captivating realm of early childhood, children embark on a wondrous journey of discovery and growth. One fascinating aspect of their cognitive development lies in their engagement with schematic learning styles. Derived from the works of Chris Athey, John Dewey, and Jean Piaget, these learning styles provide valuable insights into how children organise and make sense of their experiences. At The Curiosity Approach® we aim to explore the essence of schematic learning styles and delve into the different types of schemas found in early years. By understanding the power of play and the repeated behaviours associated with each schema, we uncover the magic that fuels children's learning and development.

Understanding Schematic Learning Styles:

In early childhood, schematic learning styles offer a profound understanding of how children absorb, interpret, and construct knowledge through play. They are recognised as repeated patterns in behaviour, urges and compulsions children have to discover and find out about the world around them.

The transportation, trajectory, containing, enveloping, connecting, and transforming schemas provide a glimpse into the rich tapestry of children's cognitive development. By recognising and embracing these schemas, educators and caregivers can create nurturing environments that allow children to explore, create, and make connections between their experiences and the world around them. At the Curiosity Approach® we believe that by honouring the magic of play and the repeated behaviours associated with each schema, we unlock the potential for holistic learning and growth in the early years.

The Different Types of Schematic Learning Styles:

1. Transporting Schema:

Transporting schema involves the exploration and understanding of objects and their movement from one place to another. Children with a transporting schema often engage in activities such as carrying toys, pushing objects, or moving items around. Ever noticed how some children love to fill handbags and purse and carry bits and bobs around the setting?

This schema allows children to develop their coordination, spatial awareness, and problem-solving skills. As they engage in transporting schema activities, they learn about weight, balance, and cause-and-effect relationships. For example, a child may discover that a heavy object is more challenging to carry than a lighter one or that pushing a toy car harder makes it go faster.

Through transporting schema, children develop an understanding of object permanence, which is the concept that objects exist even when they are out of sight. This schema also promotes imaginative play, as children often incorporate transporting activities into their pretend play scenarios, such as pretending to be a delivery person or a construction worker.

Trajectory Schema:

Trajectory schema is another cognitive framework that emerges during early childhood. It involves children's fascination with the path and movement of objects, particularly in a linear or curved motion. Children with a trajectory schema may enjoy activities such as throwing objects, rolling balls, or watching the movement vehicles and toy cars. Children who have a fascination with running water or knocking over of blocks, the compulsion of running down corridors can mistakenly be considered as negative behaviour, but children may just have that URGE FOR MOVEMENT, momentum. Exploring the force, speed and movement of themselves and things.

Through trajectory schema, children learn about speed, distance, and direction. They experiment with different angles and forces to understand how objects move in predictable ways. For instance, a child might observe that throwing a ball at a higher angle makes it go higher, or that rolling a toy car down a ramp makes it go faster.

This schema also contributes to children's understanding of cause and effect. They learn that specific actions result in predictable outcomes. Furthermore, trajectory schema encourages children to engage in physical activity, helping them develop their gross motor skills, coordination, and spatial awareness.

2. Containing Schema:

The containing schema manifests as a fascination with enclosing objects and spaces. Children with this schema are captivated by the act of putting objects into containers, building forts, filling and emptying. Through these repeated behaviours, they explore the concepts of containment, boundaries, and spatial relationships.

According to Dewey (1916), "Children exhibiting a containing schema often engage in activities that involve organizing objects into boxes or creating structures that provide a sense of enclosure." This behavior reflects their intrinsic desire to comprehend the notion of containment and its implications.

3. Enveloping Schema:

The enveloping schema involves a child's enchantment with wrapping, covering, or hiding objects and themselves. They may engage in activities such as wrapping toys in blankets, hiding under bedsheets, or creating imaginative hideouts. Through these repeated behaviours, children explore concepts of concealment, protection, and transformation.

Piaget (1952) illuminates this schema, stating, "The enveloping schema represents a child's desire to create a secure and transformative space. It allows them to explore the world around them, making connections between objects and their physical properties." This behaviour unveils their innate curiosity and their quest to comprehend the world through their personal actions.

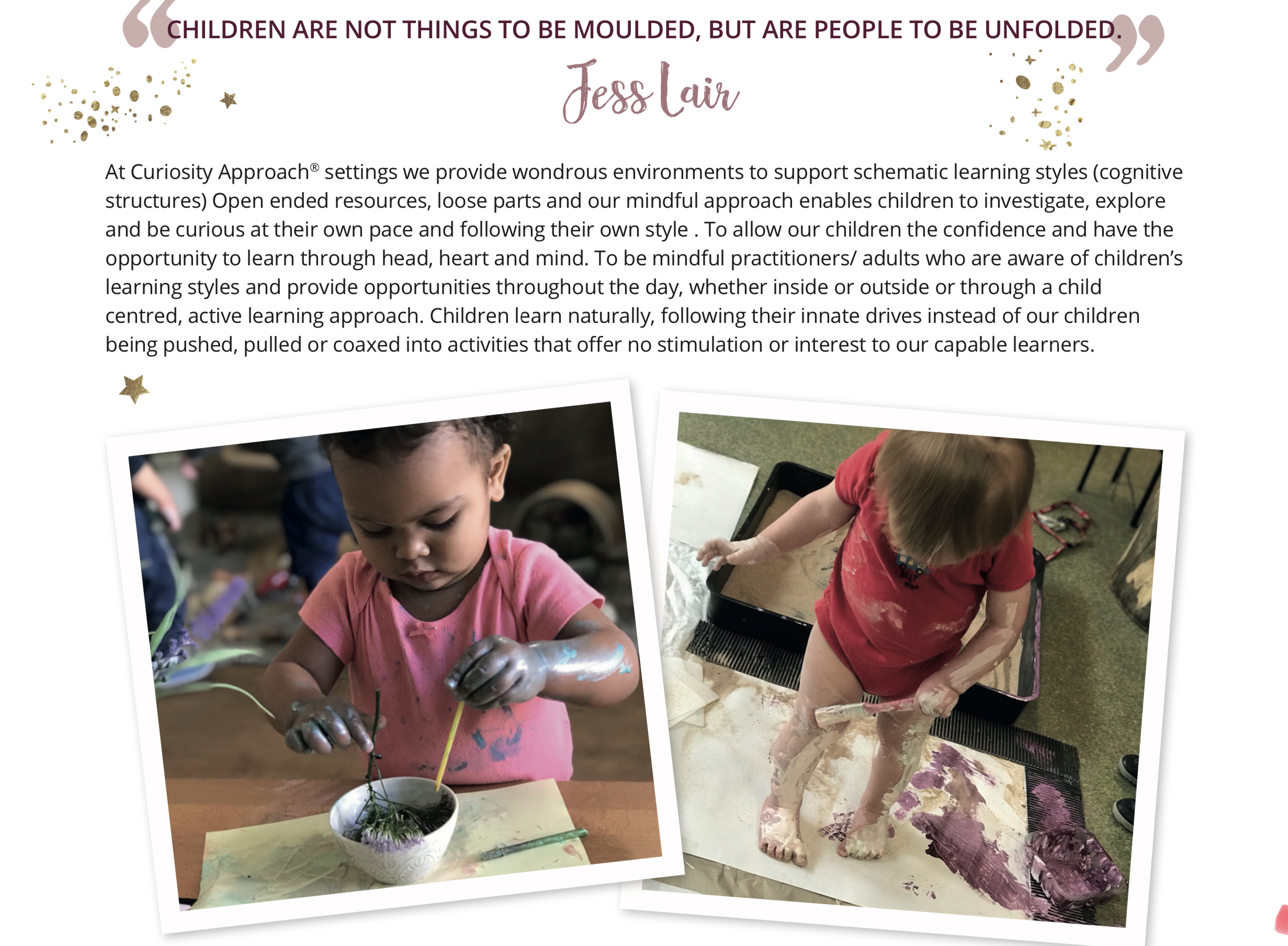

Children way also have an urge to paint themselves.

4. Connecting Schema:

The connecting schema revolves around children's fascination with linking and joining objects, ideas, or experiences. During play, children with this schema may engage in activities such as building intricate structures with blocks, creating elaborate storylines that interconnect various characters and events, or assembling puzzles. Through these repetitive actions, they explore the concept of connections, patterns, and cause-and-effect relationships.

Athey (2007) emphasises the significance of the connecting schema, stating, "Children exhibiting a connecting schema often demonstrate a strong desire to link and combine elements in their play. They may enjoy activities that involve building, sorting, or creating narratives with interconnected plotlines." This behaviour showcases their innate drive to make sense of the world by establishing meaningful relationships between various elements.

5. Transforming Schema:

The transforming schema revolves around children's fascination with change, metamorphosis, and the exploration of cause-and-effect relationships. During play, children with this schema may engage in activities such as pouring and mixing substances, experimenting with different materials, or engaging in dramatic play where they transform into various characters. Through these repeated behaviours, they explore concepts of transformation, states of matter, and the consequences of their actions.

Piaget (1952) highlights the transformative nature of play for children with this schema, stating, "The transforming schema allows children to explore the world by manipulating materials, observing changes, and understanding cause-and-effect relationships. It empowers them to see the possibilities of transformation in their surroundings." This behaviour or reflects their innate desire to experiment, discover, and witness the power of their own agency.

Image is credited to Knighton Day Nursery

To summarise - Schema in play refers to the repetitive patterns of behaviour and thinking that children exhibit during their play experiences. These patterns reflect the child's cognitive development and understanding of the world around them. Understanding and recognising these schemas can help create powerful play spaces that cater to children's individual learning styles and promote their overall development.

By spotting and understanding schemas in play, educators can create powerful play spaces that cater to children's individual learning styles. They can provide materials, activities, and experiences that align with the specific schemas children are exhibiting, allowing them to explore and develop their understanding further. This approach promotes children's cognitive development, fosters their engagement in meaningful play, and supports their overall learning and growth.

References:

Athey, C. (2007). Extending Thought in Young Children: A Parent-Teacher Partnership. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. The Macmillan Company.

Piaget, J. (1952). The Origins of Intelligence in Children. International Universities Press.

We hope you have enjoyed this blog, please go to www.thecuriosityapproach.com for a wealth of other informative articles and images from our Curiosity Approach® settings

For more information and knowledge, check out our Curiosity Approach®App The first 30 days are completely FREE

Get this EZINE FROM OUR APP

This blog is protected copyright protected.

Take the score card quiz here https://thecuriosityapproach.s...